Season 1: Episode 7

Oh, Give Me A Home

In the last episode of season one, we travel to the Blackfeet Nation and the Oakland Zoo, and we return to Gardiner, Montana, to we meet some of the only people in America who are growing up with wild bison. And we tackle some of the big questions driving this whole investigation: what is our future with this animal? How does that connect with our history? Can America ever have wild, free-roaming bison again? Should we try? Why, or why not?

Read More

Blackfeet Nation

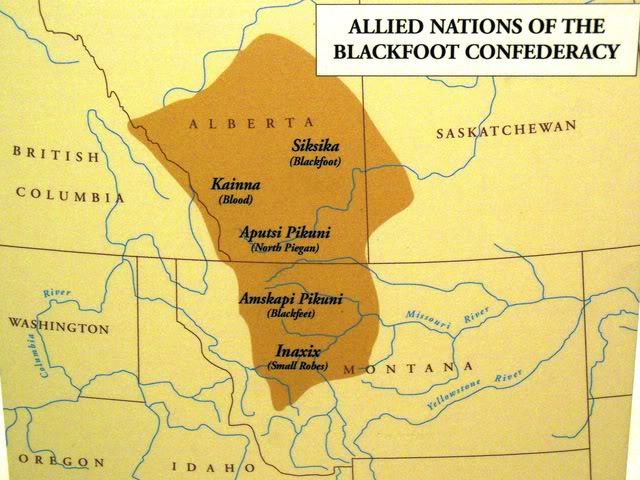

Read more about Montana's Blackfeet Nation and the whole Blackfoot Confederacy:

Badger-Two Medicine Region -- one of the areas where bison may be returned to the landscape

10 Things You Should Know About the Blackfeet Nation—rom Indian Country Media Network

Iinnii Initiative & ITBC

Learn more about the Iinnii Initiative here and in the video to the left.

The mission of the InterTribal Buffalo Council is "restoring buffalo to the Indian Country, to preserve our historical, cultural, traditional and spiritual relationship for future generations." Ervin Carlson is the president of the board of ITBC.

Elk Island and the Oakland Zoo

Scroll through the pictures above to see photos of bison being returned from Canada's Elk Island National Park to the Blackfeet Nation. Twenty of these animals will be heading to the Oakland Zoo sometime this year.

Credits

Thank you to our sponsors, especially Montana Public Radio, and the many individual donors who are helping to create Threshold. Travis Yost is the genius behind the rest of the music for this entire season. Big thanks to him and big thanks to Jimi Nasset for the use of his song in our bison-in-Oakland section in this episode. Finally, huge thanks to Team Threshold for their tireless work here. Nick Mott, Zoe Rom, Jackson Barnett, Nora Saks and Josh Burnham—thank you. And thanks to you, for listening.

Transcript

[00:00] INTRODUCTION

MUSIC: Canadian National Anthem

AMY: Oh, Canada. We’ve treated you so badly. You are full of bison stories, which we have completely ignored on this show. I know you’re used to this kind of narcissistic behavior from Americans, but that doesn’t make it right. So, this is my official apology to the bison and the people of Canada. Alaska? Mexico? Apologies to you as well. There was just no way we could tell every bison story that deserves to be told here.

MUSIC: Canadian National Anthem

AMY: Welcome to Threshold, I’m Amy Martin, and those of you who’ve been listening from the beginning know that bison used to roam throughout North America, and they’re being restored throughout North America too. On our website you can see a great video of bison being returned to Banff National Park, for instance. Those are plains bison – the same kind we have here in the lower 48 – but further north in Canada and in Alaska, you can find wood bison, a distinct subspecies which was also almost wiped out, and is now making a comeback. Of course, historically, both people and bison moved freely between what we now call the U.S. and Canada, and in this episode, we’re going to meet some bison that may soon do so again. And that’s not all – some of those same buffalo are heading to Oakland, California. We’re going to get a preview of their journey, and so much more, in this final episode in our first season of Threshold.

MUSIC: THRESHOLD THEME

“Bison are not allowed to go beyond a certain point and if they do they are hazed or sent to slaughter.”

“Everybody has this big dream that you can free roam and it’s going to be so good for everybody. It’s not.”

“It’s up to us to say, OK, well how are we going to do this?”

“Yes, America could live with free-ranging wild bison.”

“I don’t think in Montana there is a place for free-roaming bison.”

“Buffalo have taken care of Native Americans since the beginning of time.”

“We’re extraordinarily adaptable people and I think we’re hopeful. Bison are returning.”

[02:00] SEGMENT A

AMY: Do you remember the first time you saw buffalo?

ERVIN: Ah, I don’t even remember as a kid ever seeing buffalo.

AMY: Ervin Carlson is the buffalo program director for Montana’s Blackfeet Nation. He’s in his fifties, tall, and the cowboy hat he’s wearing makes him taller. Bison have become Ervin’s passion, but like Robbie Magnan from the Fort Peck Tribes, he didn’t grow up with them. He was a ranch kid.

ERVIN: Ah, we had cattle. Cattle and horses, yeah. So I grew up doing that.

AMY: The Blackfeet reservation is in northwest Montana, it borders Glacier National Park to the west, and Canada to the north. It’s beautiful country – one of my favorite parts of Montana. Big, sweeping, mostly treeless plains meet the craggy peaks of the Rocky Mountain Front. Today, the Blackfeet have a herd of more than 400 bison, but Ervin says when they first reintroduced the animals in the 1970s, he wasn’t all that interested in them.

ERVIN: You know like I say for them being gone so long...the connection was almost gone too.

ROSALYN: There was a huge effort to teach the Blackfeet to become farmers to become American farmers.

AMY: This is Rosalyn LaPier, we first met her back in episode two. She’s an environmental historian at the University of Montana and a member of the Blackfeet tribe. And she says this lost connection that Ervin is talking about didn’t stop with the near-extermination of the bison. Agents for the Bureau of Indian Affairs then tried to re-engineer Blackfeet culture.

ROSALYN: The Blackfeet agency had a point system where they would enumerate how many acres of wheat somebody was growing, how many acres of potatoes somebody was growing. You also got points for how clean your house was, how clean your children were.

AMY: Government officials would keep track of how many points different families earned in a year.

ROSALYN: And then there was also as part of the point system, there was also like a demerit system. So if Blackfeet had dogs – which were considered not useful -- for every two dogs it would be minus 10 points. So the things that were of value to the Blackfeet – so in the old days horses were of value, dogs were of value – they got demerits for owning them.

AMY: Rosalyn says these points would be added up, and families that had earned the most would win prizes.

ROSALYN: So people would know, you know, if you got 400 points and then your neighbor got 700 points. So it was kind of a strange reality, that literally equated your dirty laundry with points.

AMY: This was in the 1920s, when Ervin or Rosalyn’s grandparents, or great-grandparents were coming of age.

ROSALYN: That was being used as a colonial process against native people. Native people were being forced to be farmers, you know forced to till the land which they did not want to do.

AMY: So by the time Ervin Carlson was growing up, there had already been decades of concerted effort to make the Blackfeet forget their buffalo heritage.

ERVIN: And it seemed like it took me a long time just working with them to really regain that connection and just through the years that connection just grew.

AMY: Ervin is now the president of the Inter-Tribal Buffalo Council, a coalition of 58 tribes working to return bison to Indian Country. And in that role, he sees people like himself all over the U.S. and Canada, tribal people who are rejecting the colonial mindset they grew up with, and reconnecting with buffalo. He speaks very quietly, but there’s an intensity in his eyes when he talks about this.

ERVIN: That connection was gone. They hadn't been around so long that we just didn't have that they were gone a lot along with a lot of other things of our culture that were just kind of going away but now they're coming back strong and buffalo’s a big part of that....I love going to battle for these animals. And for us, for our culture.

AMY: There’s a thunderstorm storm building behind the mountains as Ervin drives me out to meet some of the tribe’s bison. We round a bend in the highway, and suddenly around 80 yearling calves come into view.

AMBI: wow...

AMY: The sky is turning an inky shade of blue behind the herd as the storm rolls toward us. We get out of the truck to take pictures before it hits.

ERVIN: These animals go into the storm. Most animals will turn, cattle and horses will turn and hump up and let the snow come to their backs. But they just – I don’t what it is, it’s just their nature, they just turn into the storm and face it, you know?

AMY: Ervin told me a story of a recent snowstorm in South Dakota that killed a lot of cattle. But no bison died in that storm. Other people told me similar stories, and there are historical accounts of this too – homesteaders who lost all of their livestock in brutal winters, while the few bison left managed to keep themselves alive.

ERVIN: I've learned a lot from these animals so I have really learned a lot, you know. Just how they live and you know how strong they are, and how family oriented they are, and protective of one another you know. So you know I've learned all those things from them you know, and how they belong here the feeling of how they belong here. And that we're one and the same. We belong on this landscape. We're from here, we originated from here, and together we belong here on this landscape. And that's how I feel.

SOUND: Lightning

AMY: The lightning starts to crackle across the sky, and the buffalo bunch together to weather the storm.

ERVIN: Now our people are really realizing that, hey, these animals are really important to us. They were part of us and we need to keep them here and build and protect them. I mean now they realize that.

AMBI: OAKLAND ZOO

ERICA: The lesson is always the same what impact humans have on our natural world.

AMY: This is Erica Calcagno of the Oakland Zoo. Yep, we just trekked from the Blackfeet reservation to the California coast. And later this year, 20 Blackfeet bison are going to make the same journey. The Oakland Zoo currently has just four bison, all females, all in their golden years. Erica is their keeper.

ERICA: We’re going to…

AMY: Oh, there’s one, I see a back.

ERICA: Alright we’re going to stop here...

SOUND: truck stopping

AMY: We are walking uphill through knee-high grass toward these very placid-looking bison cows.

ERICA: If these were the two-year-olds, we’re not walking out here. But these are the 22-year-olds. And I think we can get a little closer than this.

AMY: The zoo is located in the Oakland Hills, almost 2,000 feet above the city. There’s a ski lift type of thing running overhead. Families are riding along, looking down into the bison pasture. It’s kind of a surreal combination of wildness and city, all mushed together.

JOEL: Yeah we’ve got some poppies, and we’ve got a spectacular view of the San Francisco Bay.

AMY: This is Joel Parrot, president of the Oakland Zoo.

JOEL: And this is what really makes the Oakland Zoo special but it’s also going to be very special for the bison exhibit.

AMY: Joel and I are walking around a big, rolling field at the top of the hill. Above where the zoo’s current mini herd resides. There are pockets of trees tucked into the gullies, and we can see all of the East Bay, San Francisco, and the Golden Gate Bridge. This will soon be home to 20 bison from the Blackfeet Reservation – a new, expanded bison exhibit, designed to give people an experience of something closer to an actual herd.

JOEL: We have 750,000 guests that can come appreciate the bison and really become supporters of the project.

AMY: That project is an ongoing relationship between the Oakland Zoo and the Blackfeet Nation. Joel says the zoo will raise funds to support bison restoration on Blackfeet land, and the calves born here in Oakland will eventually be returned to the Blackfeet, to supplement their herd.

JOEL: All those calves are going to go back to the wild.

AMY: I’ve really tried to avoid anthropomorphizing bison here, but I just can’t resist taking a moment to imagine a bison calf who lives its first year or two in Oakland, and then arrives on the Blackfeet Reservation as a young teenager. It’s like a set-up for a bison sitcom, right?

MUSIC

AMY: The Oakland buffalo tries to impress its rural cousins with its hip city ways, and then gets schooled by them during the first big snowstorm. And something along these lines might actually happen in the human world. The zoo and the tribe are planning cultural exchanges, where young people from Oakland travel up to Montana to learn about bison on the reservation, and young tribal kids come down to the Oakland Zoo, to help visitors understand the importance of bison to Blackfeet people – not just historically, but now, and in the future.

ERICA: We need to teach these lessons. So that they can be carried on.

AMY: This is Erica Calcagno again.

ERICA: It’s a very similar lesson to tigers, to lions...just the moral and ethical question of what impact do we want to leave on the world? We’re the biggest influence on species survival or lack thereof in the world. So teach the kids young, get them to know these animals, get to know their value.

AMY: Right on cue, possibly the world’s cutest little girl, maybe three years old, plops down in the middle of the sidewalk right in front of us.

ADORABLE SMALL HUMAN: I want to see lions and giraffes.

AMY: Lions and giraffes! Awesome! (laughs)

ERICA: And it's that age. That you need to – little pigtails, pink dress, red shoes, and flopping down on the ground – by the time she's sitting in this seat, there may not be any bison, there may not be any tigers, there may not be any lions or reptiles. So, I think our job is to communicate those lessons and communicate them strongly. Otherwise we're up the creek. (laughs)

AMY: Which creek exactly is that? (laughs)

ERICA: Yeah...starts with an s. Not sure after that.

AMY: All of these journeys back and forth between California and Montana will happen in trucks – it’s not like the bison are going to be marched across the country. And back on the Blackfeet Reservation, Ervin and I are sitting in his truck now, watching the herd huddle together in the wind and the rain.

SOUND: Thunder and rain

ERVIN: You know, those are the hardiest animals you can have right there. They can survive anything.

AMY: A couple of episodes ago when we were talking about the Pablo-Allard herd, I mentioned that those animals would be important again later. Here’s how this loose thread gets woven back in. The Pablo-Allard herd was started by members of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes at the turn of the last century. It became one of the largest private conservation herds in the country. And the CSKT don’t live all that far from the Blackfeet, and the animals used to start the Pablo-Allard herd actually came from this area, east of the Continental Divide. When that herd was sold to the Canadian government, those bison went to live in Canada’s Elk Island National Park, more than 400 miles north of the border. They lived there for more than a hundred years, until 2016, when these calves Ervin and I are watching now were returned here from Canada.

ERVIN: They were gone for so long but now we're there bringing them back. So it's a big hope that we can keep keep our culture and our history alive.

AMY: The Blackfeet had a ceremony to welcome the animals back. Ervin says it was a really big deal for the tribe.

ERVIN: It’s...bringing back our past and keeping it intact for future generations. Here. Here for them. In the future. So it's good.

AMY: Montana’s Blackfeet tribe are part of a four-nation confederacy, and the other three parts of that group are in Canada. Together, they’ve formed the Innii Initiative – “innii” means “bison” in Blackfeet. And this is a plan to return bison throughout Blackfeet territory, on both sides of the border. Ervin sees a day when the bison might be free to cross another border too – the eastern boundary of Glacier National Park. Glacier’s superintendent has expressed his support for the idea, and Glacier actually connects to Waterton Lakes National Park in Canada. So it’s possible that this whole area could become a home for a herd of free-roaming international buffalo.

MUSIC

AMY: Like Robbie Magnan of the Fort Peck Tribes, Ervin sees this as an important way for his community to build their economy. Millions of people visit Glacier every year, and he hopes to take some of them on tours to see the herd, or to watch demonstrations of hide work. He says reconnecting with the bison in this way can help the Blackfeet people regain the self-sufficiency that was taken from them when the bison were nearly lost.

ERVIN: The work isn’t done. It’s just beginning. It’s only the beginning.

AMY: We’ll have more after this short break.

Break

[15:28] SEGMENT B

ABIGAIL: Um, I’m sure you’ve seen our football field. It’s usually covered in poop.

AMY: Welcome back to Threshold, I’m Amy Martin and I’m with Abigail Dean, a sophomore at Gardiner High School.

ABIGAIL: Ahm, huh, so our school’s detention – if you get detention you have to go scoop poop off the football field.

AMY: Gardiner is where we started this season – it’s the small town perched on the northern border of Yellowstone National Park where I met Rick Wallen and we went out to count bison. I haven’t extensively researched this, but I’m going to go out on a limb here and say I’m pretty sure Gardiner is the only place in the country where cleaning up after a herd of wild bison is how kids serve detention.

ABIGAIL: It’s very funny seeing somebody out there after school just picking up all the poop and putting it in the bucket. (laughs)

AMY: Many times over the last 18 months, as I watched bison herds in various places, I had the thought: if you only knew how many meetings and phone calls and emails and news reports and lawsuits and conversations we’ve had about you. And most of those arguments involve theoreticals: what the animals might do, where they might go, how they might affect us if we had more of them around. But the Gardiner kids can actually answer some of those questions with real-world experience. They’ve been living with wild bison their whole lives, and since they’re some of the only Americans who can say that, it seems like their perspectives are worth paying attention to. So I asked them – what’s it like to live with these animals? What do you think you can remember about it?

ABIGAIL: We were out at recess one day, and I just remember everyone, all the teachers started yelling at us to get off of the playground, to get back to the school. And it was the scariest thing, because there were just tons of bison, running in from the side. And they all came into the playground – it was just a big stampede I guess, it was crazy. And we just watched them for probably 20 minutes, there were babies everywhere. It was amazing.

AMY: Wow, like what you were feeling during that?

ABIGAIL: I was scared. They’re big animals. And it was very scary to see them come at me while I was running up the hill, away from the playground. But it was really exciting to see them come, and just to know that we lived with them in peace and that they could come onto our school playground whenever they wanted to. It was crazy. And now I look at them just as usuals.

AMY: All of this sounds pretty exotic and almost kind of crazy – bison on the playground? But up until just a few hundred years ago, almost every kid in North America grew up with bison. Generation after generation, for tens of thousands of years. So, when you think about it this way, these kids in Gardiner are the normal ones, and the rest of us, who’ve grown up with no knowledge of bison, are the weirdos here.

ZANDER: Like going out to the bus stop for example in the winter, uhm, it’s still dark out when I go out. And so it’s always, checking behind your back and just making sure that there’s no bison, which would not be fun to encounter at 7 o’clock in the morning.

AMY: This is Zander Opperman he’s an 8th grader, and he says even though it can be a little stressful sometimes, overall, he likes living with bison.

ZANDER: Sometimes it definitely does make you feel small. Ahm, you know, you have a 2,000-pound animal which can run faster than you...and it can survive subzero temperatures without putting on anything else except for like a bit extra fur. And, you know, it can feed in like three feet of snow. So it definitely is like, wow, maybe, you know...maybe we aren’t as tough as we all dream we are.

AMY: So it sort of, uhm, gives you some humility.

ZANDER: Yeah, mm-hmm.

CAITLIN: They’re, they’re a symbol, I think, but they’re also just...giant (laughs).

AMY: Caitlin Cunningham is a senior.

CAITLIN: And I mean they’re totally like enormous and they’re...I think they’re really cool, just physically.

AMY: Caitlin and her family raise cattle just outside of Gardiner, and she’s concerned about the possibility of brucellosis being passed on to her livestock. But, she’s not advocating for totally removing bison from the landscape – she just wants to figure out the best places for them to go.

CAITLIN: You know we just want to be respected, and we just want to show that we are educated on the issue, on all aspects, because we do like bison. We like having them around. But it kind of comes down to where to draw the line. Like, literally, where to draw the line.

DANI: I think it’s easier for us to understand a lot of like wildlife controversies that might go on other places because we have so many here.

AMY: And this is Dani Hatfield, she’s also a senior.

AMY: A lot of schools obviously have fire drills, or earthquake drills in some places. Did you guys ever have bison drills, or wild animal drills?

DANI: Not exactly no, we’ve had warnings after school and such that, you know, there’s bears in the area. But with bison it was just...make sure they’re not right outside the door, and not too close.

AMY: This combination of awareness and nonchalance seems to be the prevailing attitude toward bison among these students. They were noticeably calmer and less prone to extreme statements than many of the adults involved in the debate. And I think that may have something to do with the fact that for them, bison are real things – not remote icons, or scary demons, or once-in-a-lifetime vacation experiences. To the kids of Gardiner, bison are 2,000-pound vegetarians that poop on their football field, and sometimes show up on their lawns, and don’t want to leave.

DANI: We had like an old antique horn from a truck that we’d honk at ‘em, and that got ‘em for a while. But by the end we were so desperate to keep ‘em out we were like playing rock and roll music really loud, and bagpipe music, and…

AMY: Were they more likely to move when they heard rock, or when they heard bagpipes?

DANI: Ah, the bagpipes worked better.

AMY: Most kids in the United States today grow up without having any direct contact with wild animals. And maybe this makes them safer. But whenever we insulate ourselves from risky experiences, we also sacrifice some rewards. And whether they like the bison or not, all of these students are learning things from them.

MUSIC

AMY: Do you think controversy is inevitable when people and wildlife come together?

DANI: I think controversy is often inevitable when it’s just people together. But...yeah…

AMY: When Europeans came to North America, they brought a myth with them – a story that felt like a fact. In that story, human progress inevitably involved control over the non-human world. Making places and creatures bend to their will. And what didn’t bend, had to be broken. Bison, and the people who depended on them, didn’t bend.

ERVIN: You know what it is, is to learn to respect them.

AMY: Again, this is Ervin Carlson of the Blackfeet Nation.

ERVIN: To respect them. That they're a part of us, they're a part of our land, part of our history. Everybody here, you know. If you want to say you're a part of this, this country here then and respect that they were part of this country too. You know and so they belong just like everybody else belongs. They were here before everybody else. And so why can't we keep that history there? You know.

MUSIC

AMY: The idea that human progress requires dominance of the natural world is still so powerful in our society that it’s really hard to see outside of it, to recognize it as one worldview among many. But, even if we can’t quite imagine it, some part of us is often hungry to live another way. Trying to control everything all the time is exhausting. Just like Zander said, sometimes we want to be reminded that we’re not so tough as we all dream we are.

KEITH: We can invent many many ways to live and we're not done inventing ways to live. We're barely starting.

AMY: This is Keith Aune of the Wildlife Conservation Society, we’ve met him in some previous episodes. Keith is from Dutton, Montana, a very small town in the north-central part of the state, and he says it’s partly the experience of watching his own rural community struggle to stay alive that has convinced him that this old way of approaching nature has to change.

KEITH: And I'll tell you who the curmudgeons are, the curmudgeons are the guys that are sitting there still saying, oh it's been that way for a long time forget it, get over it. No it isn't. Humans change. They've changed for eons they’re going to change again. And the tribes themselves -- they're all coming to this epiphany too and saying, you know what, maybe we don't have to live the way we were told when we were stuck in residential school and taught, you know, the way of the missionaries. We can actually take that context and apply our old knowledge blend that into something new and different. And that's what's happening. It's already happening.

AMY: Who would ever guess this little farm boy from Dutton would have such radical ideas.

KEITH: Well, you know, that's probably why.

AMY: I want to leave you with one last story. It’s something that happened when I was at the American Prairie Reserve. During my visit there, some commercial bison ranchers came for a tour, and they let me ride along with them. One of them was a gentleman named Steve Mitchell. Steve looks like he walked right out of the set of a western movie – cowboy hat, flannel shirt, suspenders – he even has the big bushy mustache. We spent the morning driving around together, looking at the bison – he told me that over many years of working with them, they had made him a better person. I wanted to ask more, but I didn’t really have a chance, and then the tour was over, and it was time to shake hands and walk away. But, when I was back at my truck, loading up my stuff, Steve suddenly appeared next to me, and he half-whispered that he wanted to tell me something. So, I asked him to wait a second while I turned my recorder back on, and then he said this:

STEVE: I don’t think we really own the land. We just get to use it.

AMY: Yeah. Who do you think owns it?

AMY: Steve’s eyes were filling up with tears, so he kind of just mouthed his answer.

AMY: Nobody?

STEVE: Nobody. (whispered)

AMY: What is that making you feel?

STEVE: Well, I just want to make it better than it was when we got it.

AMY: Steve seemed sort of beside himself, like he wasn’t expecting this big wave of emotion and he didn’t know what to do with it, so he just gave me a quick hug.

STEVE: Sorry...

AMY: And then he walked away, as suddenly as he’d appeared.

MUSIC

AMY: As I was driving away from the American Prairie Reserve, I couldn’t get Steve out of my mind. Why was it so important for him to tell me that? The conversation had the feeling of a confession, like he was sharing something blasphemous. And maybe it kind of was. Saying “nobody really owns the land, we just get to use it” – is actually kind of a radical statement, it’s a rejection of our whole paradigm of dominance and control. I started to realize that Steve may have been trying to tell me this all morning, as he shared stories of working with bison, and how they’d made him more patient, and humble. In our country, we tend to celebrate our power to change things. But Steve wanted me to know that bison had shown him a different kind of power. The power of letting himself be changed.

MUSIC

SOUND: Bison grunting, birds chirping

AMY: We have pictures and videos and all kinds of additional information on our website – threshold podcast.org. We also have two quick corrections: we neglected to mention the Book Cliffs herd when we were talking about the main wild herds in the lower 48 – that’s a herd in eastern Utah and western Colorado. And we said that Yellowstone National Park ran the quarantine pilot project when it was actually run by the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service and Montana Fish Wildlife and Parks.

Credits

AMY: Thank you to our sponsors, especially Montana Public Radio, and the many individual donors who are helping to create Threshold. Travis Yost is the genius behind the rest of the music for this entire season. Big thanks to him and big thanks to Jimi Nasset for the use of his song in our bison-in-Oakland section in this episode. Finally, huge thanks to Team Threshold for their tireless work here. Nick Mott, Zoe Rom, Jackson Barnett, Nora Saks and Josh Burnham – thank you. And thanks to you, for listening. We’re already planning season two, and season three – find out how to support the show and sign up for our mailing list at thresholdpodcast.org.

Threshold Newsletter

Sign up to learn about what we're working on and stay connected to us between seasons.