Season 1: Episode 5

Heirs to the Most Glorious Heritage

"We have fallen heirs to the most glorious heritage a people ever received, and each one must do his part if we wish to show that the nation is worthy of its good fortune."

Theodore Roosevelt

In 1908, the National Bison Range was created by carving 18,000 acres out of Montana's Flathead Reservation. Now, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service says it is willing to transfer the land back to the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. But, a lawsuit has been filed to stop the proposed transfer. In this episode, we meet tribal members who feel they are the rightful stewards of the land and the historic bison herd, and others who are trying to stop the transfer.

Read More

Update to the National Bison Range

Bison Range Working Group

This site, created by the CSKT, is where you can find the draft legislation, public comments on the proposed legislation, responses to the comments, and other news about the potential transfer of the National Bison Range.

PEER Lawsuit

Read the lawsuit filed by the group Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility on May 23, 2016.

Environmental Impact Statement

On January 18, 2017, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced its intention to create two separate but related documents for the National Bison Range—an environmental impact statement (EIS) and a comprehensive conservation plan (CCP). Here's the announcement. There will be opportunities for the public to comment throughout this process. We'll do our best to keep you updated on those opportunities here.

Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes

The Rez We Live On is a great resource if you want to learn more about the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. A few videos from that site are embedded to the left. You can also find information at the CSKT main website and their website devoted to The People's Center.

Racial, Ethnic, and Religious Tension in the Flathead Valley

The report "Drumming Up Resentment," published by the Montana Human Rights Network, documents the history of anti-Indian movements in Montana from 1970 to 2000.

This is the website for Love Lives Here, a Flathead Valley human rights organization mentioned in this episode.

Other Reports

"Hundreds Gather Against Hate in Whitefish," Montana Public Radio, January 2017

"Neo-Nazis Submit Incomplete Application to March in Whitefish," Montana Public Radio, January 2017

"Flathead Valley Celebrates Poignant Martin Luther King, Jr. Day," Montana Public Radio, January 2017

"Islam, Race and the Battle for the Flathead Valley Soul," Montana Public Radio, November 2016

"Fight Brewing Over Proposed Transfer of National Bison Range," Montana Public Radio, June 2016

"Anti-Indian or Not? Controversial Conference on Tap in Kalispell," Missoulian, September 2015

"Indian Tribes Aim to Manage Bison Range," Washington Post, July 2003

"Bison Rage," Missoula Independent, June 2003

Historic News Reports

"Allards Famous Herd of Buffalos Snapped by Standards Camera," Anaconda Standard, 1899

"To Preserve Bison," Yellowstone Monitor, 1908

Other Related Links

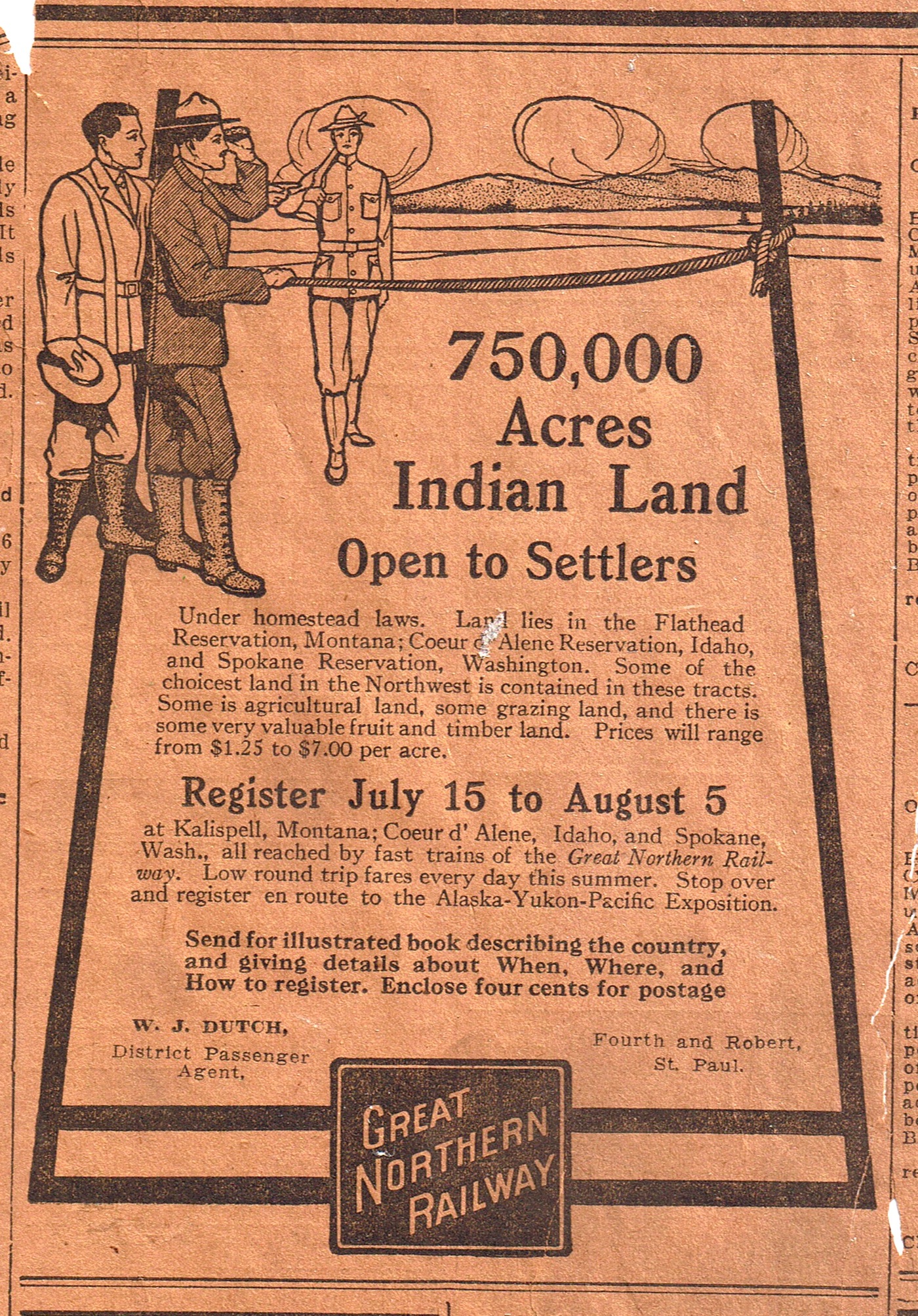

The history of allotment on Indian land is probably worthy of a podcast unto itself. The story of the National Bison Range is just one part of that larger history of land loss on the Flathead Reservation. Here's one place to start if you want to learn more.

The Goodnights of Texas helped to save some bison from the southern herds, and then later donated some animals to the National Bison Range. A few other private ranchers also contributed to the national herd. Here's more about the Goodnights.

Alicia Conrad was the granddaughter of the Conrads who bought bison from the Pablo-Allard herd, and then sold some of those animals to help start the National Bison Range. She died in 2010; her obituary from the Daily Interlake helps connect some of the dots we touch upon in this episode.

Other Montana Tribes

American Indians 101 and Essential Understandings Regarding Montana Indians were created by the Montana Office of Public Instruction. Find more tools at their Indian Education for All site.

Credits

Threshold is produced by me, Amy Martin, with help from Nora Saks, Jackson Barnett, Zoe Rom, Nick Mott, and Josh Burnham. Special thanks to Michael Wright, Jessica Fjeld, Daniel Etcovitch, Christopher Bavitz, Audrey Adu-Appiah, and Mike Meloy for their help on this episode. Music by Travis Yost.

Transcript

[00:00] INTRODUCTION

SOUND: Footsteps on gravel

AMY: Hi there.

JANE: Hello.

AMY: I was wondering if I could ask you a couple of questions. I’m a radio reporter and I’m working on a story about the National Bison Range.

JANE: ....right OK, we’re just looking for rattlesnakes.

AMY: Oh, you’re looking for rattlesnakes? OK…

AMY: Welcome to Threshold. I’m Amy Martin and I’m with Jane Heppel, and her husband Bob. We had all pulled over at a highway rest stop where you can look right into the National Bison Range. This is a beautiful piece of land – 18,000 acres of quiet, grassy hills in northwest Montana that serves as a home not only to bison, but also big horn sheep, elk, deer, all sorts of birds, and yes...rattlesnakes.

JANE: There’s a sign up. Sorry, we’re all the way from England. We’re not used to seeing signs saying, “danger rattlesnakes.” So I’m a bit spooked.

AMY: Well, don’t worry...they’re not going to come creeping out…

JANE: Oh good, oh good.

AMY: I get it. Every time I stop at this place I can’t resist taking a picture of that sign. And the view behind it – it’s one of my favorite views in Montana. The stunning peaks and glaciers and waterfalls of the Mission Mountains.

JANE: We saw a big star on the map and it said, “stop here for a scenic view.” And boy is it a scenic view.

AMY: When you stand at this spot, your eye is naturally drawn to the dramatic mountains just to the east of this spot. You can almost forget to look at the lower, rounded mountains that are just to the north. But if you do, and if you’re lucky, you sometimes get a special treat. And today is one of those days.

JANE: We didn’t realize, and that was a bonus, to actually see a herd of bison.

AMY: Have you ever seen bison before?

JANE: No.

AMY: And what do you think of them?

JANE: They’re amazing, aren’t they? We’re on our way to Yellowstone, and hoping to see them there as well.

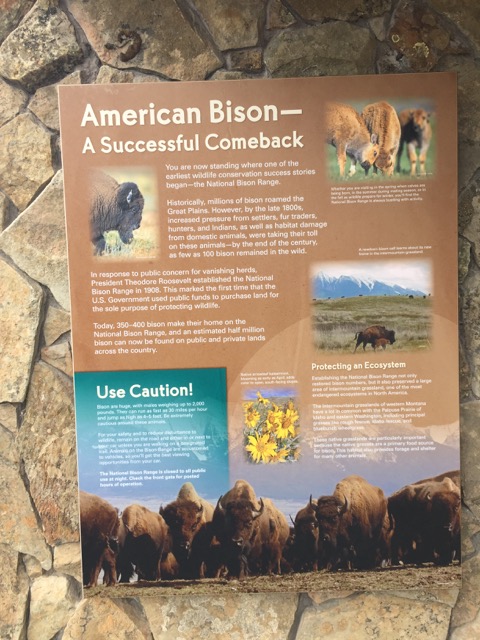

AMY: The National Bison Range sits right along one of the main routes between Glacier National Park and Yellowstone. It’s much smaller and less famous than those giant parks, but it has a very important place in the story of the American conservation movement. It was founded in 1908 for the express purpose of preserving the bison. This was in the early days of conservation, just as people in the United States were starting to realize how much had been lost in the previous century, and that if we didn’t make conscious efforts to save species and habitats, they could be wiped out. So there’s a lot to celebrate about this place – we preserved this beautiful landscape, we made a refuge here for wild animals. But there’s a dark side to it too. Because, even as these early conservationists had the foresight to try to make a place to save this animal, they seemed to ignore the rights of the people who were living here. And that injustice has ricocheted down through the decades, and is still not resolved today.

MUSIC: THRESHOLD THEME

“The term “vanishing” is a very important term.”

“We’re losing so much wildness.”

“Bison made it through that bottleneck but just barely.”

“We are not a bunch of people out here that don’t care about wildlife.”

“You definitely have to have respect for the bison.”

“Their resilience is extraordinary.”

“You do have this eerie parallel in terms of the herding up of Indians and the herding of bison.”

[03:15] SEGMENT A

AMY: Rich Janssen looks annoyed. We’re sitting across from each other on a gorgeous summer day at a picnic table not far from where I met Jane and Bob. Rich has close-cropped hair and a no-nonsense attitude. Just across the highway from us, we can see the thing that has him frustrated.

RICH: ...seeing the mighty bison, the American bison, commonly called buffalo by the Europeans, “que-quay” in the Salish language.

AMY: There are a few dozen bison in view – their dark shapes stand out against the bright green grass. It’s early June, which means there are babies here too – a handful of red calves are hopping around on the hillside while their moms are busy grazing.

RICH: Yeah, that’s a prehistoric animal that thrives, and is very hearty, and obviously was not driven to extinction like they tried, and you can see how well they’re doing right now. It’s pretty neat to see that animal walking along the side hills of the Bison Range. That you see them grazing, nonchalantly.

AMY: It’s not the bison that are making Rich frown and furrow his brow as he talks to me. It’s the story of the place where they’re living – the National Bison Range. It’s surrounded on all sides by the Flathead Reservation, the home of the Salish, Kootenai and Pend d’Oreille tribes, who are known collectively as the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, or the CSKT. Rich grew up here. He’s a tribal member and the head of the CSKT‘s natural resources department, which means he’s in charge of all sorts of wildlife projects across the reservation’s 1.2 million acres.

RICH: We essentially manage the entire reservation for wildlife. We manage the black bear population, the white-tail deer, the mule deer, the moose, the elk. Grizzly bear conservation area – beautiful grizzly bears, and one of the largest populations in the lower 48. And that’s right in our backyard.

AMY: But this other part of his backyard -- the 18,000 acres that make up the National Bison Range – this land has been declared off limits to him. In 1908, the National Bison Range was carved out of the Flathead Reservation and Rich’s ancestors were excluded from having any kind of management role here. And the tribes still don’t have authority over that land today.

RICH: I mean why not? Why wouldn't you have the stewards, the original stewards of the bison come back and manage the bison for the American public. Smack dab in the middle of our reservation, you know, ahm...

AMY: So, yeah? Why wouldn’t you? Why aren’t the tribes who’ve lived in this valley and hunted bison for 12 thousand years – why aren’t they in charge of managing this buffalo herd, and the elk, bighorn sheep, deer and other wildlife on these lands? Well, to find the answer to that question you have to look somewhere you might not expect. You have to look at the birth of the American conservation movement.

ROB: President Teddy Roosevelt had the ambition to save the bison.

AMY: This is Rob McDonald, the communications director for the CSKT. He’s sitting at the picnic table with us. And he’s glad that Teddy Roosevelt wanted to protect the bison from extinction. But he says there’s an irony built into those conservation efforts that often gets overlooked.

ROB: Luckily for him our tribal membership back then had already done some conservation efforts to bring animals over and get herds going.

AMY: In the late 1800s, the Flathead Valley tribes saw what was happening to the bison and decided to bring several calves back to the reservation from their traditional hunting grounds east of the Continental Divide. This herd grew into one of the largest privately held bison herds in the country – it was known as the Pablo-Allard herd for the two ranchers who owned them. These men were tribal members, and for a time, the bison roamed freely throughout the reservation. But when white settlers began to move into the area, the herd was split up. The bulk of the animals were sold to the Canadian government in the early 1900s – and hang on to that detail, because that’s going to become important in our next episode – but some of the bison went to a wealthy white family in the valley, the Conrads. Now enter Teddy Roosevelt looking for a good place to start a bison refuge.

ROB: His scouts came and looked for land to be the National Bison Range, to save the animal. And he selected this site so, ahm, fair and square he stole the land...is an edgy way to put it. (laughs)...but...it was kind of a free for all. Land in our possession against our will was being taken for all kinds of purposes. This was part of that.

AMY: The Conrad family sold some of the animals from the Pablo-Allard herd to help start the National Bison Range. So, these animals that had been preserved by the tribes ended up back on reservation land. But now, this land – and the animals – were in the hands of the federal government.

AMY: Obviously this was not a friendly takeover of the land. So what happened? I mean, what did the people at the time do to try and stop it? Did they feel like they had an avenue to try to stop it?

ROB: Well keep in mind at this point in time we were not considered U.S. citizens. We had no voice politically. We did voice our concerns loudly. It's been documented and recorded, and there was no obligation for them to listen to us. So they told us, you know, move. Get out of the way. This is what this is going to be. And we had no choice but to follow along. Yes we, we had objections. But again, no power.

AMY: This kind of thing happens all over the country, as I’m sure you know. But the fact that this piece of land was taken to preserve bison is one of the more bizarre versions of that familiar tale. Put yourself in the position of the people of the Flathead Reservation. You watch the buffalo get massacred in enormous numbers by these white men. Some of your own people help to save the animals. Then, some other white men come and say they’re going to save this animal. And to do it, they’re going to boot you off of the land you’ve lived on for thousands of years – land they promised was yours just 53 years before.

ROB: It’s smack in the middle, kind of like a heart in the middle of the reservation. And hard to miss it when you drive through.

AMY: You’ve lived with bison since... forever... but rather than asking you for advice, these men tell you to get out of the way. But no one from your community is allowed to have any input on helping this herd grow and stay healthy. The arrogance of all this would be astounding if it weren’t so common. And the thing is, it got baked into the system. The Confederated Salish and Kootenai tribes still do not have management authority at the National Bison Range. But, that might be about to change.

RICH: We most definitely are qualified to manage the National Bison Range.

AMY: This is Rich Janssen again. And he says it’s time for the National Bison Range to be returned to the tribes.

RICH: Our wildlife program is top-notch. I would put our wildlife program, our department, at any level of any other wildlife program within the state. Even nationally. You know we’ve won awards for our conservation efforts with trumpeter swans. The U.S. Highway 93 underpasses and overpasses that we put together have saved countless animals. We do a lot of work with lynx, bull trout, west slope cutthroat, I can go on and on and on.

ANNA: They have a really good tribal wildlife program. Probably one of the best in the country.

AMY: Anna Muñoz is with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the federal agency that currently manages the National Bison Range.

ANNA: We know that they are well-equipped to manage the lands, the resources that comprise the National Bison Range.

AMY: The CSKT have been pushing the Fish and Wildlife Service for a greater role at the bison range for more than 20 years. In that time, they’ve experimented with different collaborative management agreements, but in February of 2016, there was a big shift.

ANNA: We felt we could maximize conservation by transferring these lands into trust.

AMY: Anna says leaders of the Fish and Wildlife Service met with CSKT leaders to discuss the potential transfer of the National Bison Range back to tribal control – essentially, returning the land back to its pre-1908 status, as part of the Flathead Reservation.

ANNA: I think we saw the transfer of these lands into trust to really just be a unique opportunity for both the service and the tribe to provide for the continued conservation of bison, other wildlife, and the natural resources supported by these lands, while also allowing the service to focus our limited resources on high-priority landscape-scale conservation efforts.

AMY: So, the land was carved out of the Flathead Reservation against the will of the people, now the feds are ready to return it to tribal control – what’s not to like, right?

SKIP: I want a NEPA. I want an environmental assessment done. Go back and pick up the rulebook and follow the rules. And if you don’t like the rules, don’t get involved.

AMY: This is Skip Palmer. And he says – not so fast.

MUSIC

AMY: We’ll have more after this short break.

Break

[12:40] SEGMENT B

MUSIC

AMY: Welcome back to Threshold, I’m Amy Martin, and I’m sitting at another picnic table, this time at the home of Skip Palmer. Skip lives just over the hill from where I talked to Rich and Rob – the National Bison Range is just down the road. He worked in the maintenance department there for 16 years.

SKIP: Loved it. How could a person not love it? You know, you’re working with wildlife. I spent 16 years basically, amongst other things, chasing bison on horseback. Round ‘em up every year.

AMY: Skip told me he considers the National Bison Range to be a crown jewel of our National Wildlife Refuge system.

SKIP: It was put there for one reason, and that was to make sure that the bison didn't become extinct. And they've done their job quite well. Not just the bison range but all of the Refuge System.

AMY: To Skip, the fact that the National Bison Range is part of this large federal system is very important.

SKIP: And I'm going to keep saying the word “system” because all wildlife refuges in the United States are treated the same way. They all have the same rules, they all have the same regulations. Prime example: migratory bird surveys. All the refuges in the United States take their surveys at a set time and they do that the same time every year, and they do their surveys the same way every time, from the same spot, using the same thing to make sure that all of their data is the same.

AMY: Rob McDonald of the CSKT says the tribes would likely continue participating in these surveys, and in fact have been involved in them in the past. But that doesn’t satisfy Skip.

SKIP: We can't have one wildlife refugee that does its own thing, because if they do it's no longer part of the system and it don't work. It has to be that way.

AMY: I came to talk to Skip because he’s a co-plaintiff in a lawsuit that’s been filed to stop the proposed transfer. It was filed by a Washington, DC-based organization called Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, or PEER. On their website, PEER says their mission is to defend scientists and whistleblowers and protect public land, among other activities. Skip and I talked for two hours, and the main point he seemed to want to convey was this:

SKIP: I want a NEPA done. And I want an environmental assessment done.

AMY: NEPA stands for National Environmental Policy Act, a law passed in 1970 which requires in-depth environmental analysis of major actions by federal agencies. Skip says his concern is that the tribes could decide not to manage the area for bison conservation anymore. The CSKT have written draft legislation that Congress could use to authorize the transfer, and it says that the lands of the bison range will be managed – quote – “solely for the bison, wildlife and other natural resources” – end quote. But Skip says...

SKIP: NEPA. Don't go one step farther till we do a NEPA. We're not going to discuss this. We're not going to write a bill till we do a NEPA.

AMY: NEPA doesn’t dictate outcomes, it just provides information. And it’s actually not clear if NEPA applies here – I’ll spare you the technical details, but you should know that not everyone agrees with Skip about that. However, since Skip and I met, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has announced that they are going to do an environmental impact statement. But PEER is continuing with the lawsuit. So, there are now three separate but related things playing out here simultaneously: the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is doing an environmental review of the bison range – that’s number one. Number two – PEER is suing the Fish and Wildlife Service, and three, the tribes are waiting for someone in Congress to sponsor legislation to make this transfer happen. As we prepare this episode for release, it’s unclear exactly what’s going to happen or how these three different things may affect each other. Everyone’s kind of waiting to see.

SKIP: There’s nothing out there at this point that tells the tribe we want a guarantee from you that you’re going to keep it a bison range...nope, no guarantee.

AMY: Actually though, I interviewed somebody from Fish & Wildlife Service, and from the tribes, and they both said exactly the opposite, they said –

SKIP: I don’t care what they said, I don’t care what they said, I’ve got –

AMY: You don’t believe them.

SKIP: No.

AMY: The CSKT invited the public to comment on their draft legislation, and many conservation groups wrote in to voice support for the proposed transfer. The list includes the Montana Conservation Voters, the Mission Mountain Audubon Society, and many more. The National Wildlife Federation wrote that they had – quote -- “complete confidence that conservation of this herd will be a foremost consideration.”-end quote. But Skip doesn’t seem to trust that what the tribes say is what will actually happen. So...why not? Like I said, he and I talked for over two hours, and I couldn’t get a clear answer from him on that. But one thing that is clear is that he’s not the only person responding to this proposed transfer with suspicion. In addition to some supportive comments, some other people wrote in and said things like this:

MALE VOICE: “I do not trust the tribes to manage the bison.”

FEMALE VOICE: “I am getting tired of the tribes demanding things to which you are not entitled.”

MALE VOICE: “Leave the bison range in federal hands. The Indians – lazy bastards – will just screw it up.”

AMY: These are actual comments people submitted on the draft legislation proposed by the tribes, read here by our staff. And they point to the racism bubbling just underneath the surface of this whole debate. Now, I want to be very clear here – it is possible to be opposed to the transfer of the National Bison Range for any number of reasons. So I’m not saying that opposition to this proposed transfer is necessarily an expression of racism. That would be ridiculous. But, as these comments show, to talk about the opposition to the transfer and ignore race would be ridiculous too.

MUSIC

AMY: To give you a sense of the overall climate in which the proposed transfer is taking place, I want to introduce you to Elaine Willman. She’s the long-time leader of the Citizens Equal Rights Alliance, a group that the Southern Poverty Law Center says is, quote, “arguably the most important anti-Indian group in the nation.” I spoke with her on the phone in September of 2015, shortly before a gathering she helped to organize in Kalispell, Montana. She told me that whites and Indians had gotten along well until the passage of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act.

ELAINE: All the sudden great big money started coming into these tribes. And with that money was kind of a new power.

AMY: And this power is dangerous in Elaine’s eyes. In her book titled Slumbering Thundering: Confronting the Spread of Federal Indian Policy and Tribalism Overwhelming America, she writes: “What tribal governments want now is control over non-Indian rights, land, and courts.” She compares non-Indians who live in or near reservations to battered spouses – victims who are trying to love their abuser, but just keep getting beat up. In case you’re getting confused here, let me underscore that in Elaine’s view, Indian tribes are the abusers in this analogy, and white people are the victims. So the Citizens Equal Rights Alliance – also known by its acronym, CERA – organizes workshops around the country which are meant to inform and empower people who are trying to break out of this cycle of mistreatment.

ELAINE: I can tell you that every time that CERA brings an educational workshop anywhere, the neighboring tribal governments and folks start screaming the name-calling. We’re racist, we’re anti-Indian, we’re bigots.” So yes, we always have protestors. But we’re not going to be muzzled.

AMY: Why do you think you are protested wherever you hold these workshops?

ELAINE: Well, there’s not a short answer to that, Amy. I would imagine there are those among tribal leaders and governments that are really pleased with the special preferences and the unequal treatment and the full backing of the federal government to start a process that demeans all other Americans and diminishes state authorities. I would imagine that in their shoes I would just get as powerful and go as big as I could, and I would slam down anybody that was in my way. And that’s unfortunate in the United States.

AMY: So you feel like the Native American tribes are too powerful and they have too much advantage in society?

ELAINE: I wouldn’t put it that way. But I would say their duty is to take care of their people and their lands. Their duty is not to harass their neighbors. If they just did that, none of us would have anything to argue about, would we?

AMY: So that’s the problem you’re trying to combat, is harassment of non-Natives by Native governments?

ELAINE: Yeah.

AMY: And Elaine makes connections between Native American power and her perception of global threats too. In January of 2016, on a website called News With Views, she wrote a piece claiming the Obama administration was trying to merge something she calls “domestic tribalism” with Middle Eastern tribalism. Here’s a quote from that article: “We will now have wealthy little Sharia compounds on Indian reservations to add to the 190 cities designated to receive Syrian refugees. Obama is polka-dotting the entire country with Sharia enclaves to enrich Indian tribes and reflect our generous heart for immigrants. Our blind, deaf, and dormant Congress has held its nose and endorsed all of this.”

AMY: Elaine Willman moved to the Flathead Valley in 2015 to help fight a different tribal initiative – the Flathead Water Compact. I interviewed her several months before the bison range question was on the table, so I don’t know exactly where she stands on the proposed transfer. But her group, the Citizens Equal Rights Alliance, does have connections with people who’ve opposed it. CERA was formed in the late 1980s with the help of leaders from a Flathead Valley group called All Citizens Equal, or ACE. At th time, one of the leaders of ACE advocated for the termination of the Flathead Reservation. Decades later, in a 2003 Washington Post article, this same man said he was opposed to the transfer of the National Bison Range, because, quote, "It will drift away from the purpose these things were created for. The tribes will set it up to benefit the tribes, won't they? I say they are not capable of running things." This man was Skip Palmer’s father, Delbert.

MUSIC

AMY: Now of course, none of us are responsible for what our parents say and do, so I asked Skip how he felt about his dad’s organizing efforts.

SKIP: I will tell you this much. I was very proud of how my dad stood his ground.

MUSIC

SKIP: When the bison range has been managed successfully this long, why change it?

AMY: Well, OK, so here's why, from somebody else's perspective perhaps. Because the bison were here before the people were here the people who first came here had a cultural and subsistence relationship with them, and that this is some very small gesture of saying, of returning that –

SKIP: It's not, it's not a small gesture. It is a gigantic gesture because of the can of worms that it opens up.

AMY: As I listen to this part of our conversation now, I think Skip is right. I think it might be more than a small gesture. Re-evaluating who has a right to manage the National Bison Range just might open up a can of worms that many people would prefer to keep sealed shut.

MUSIC

AMY: There are many forces at work in the Flathead Valley. There’s a group called Love Lives Here, whose stated mission is to create an open, accepting, and diverse community. And many people who submitted comments about the proposed transfer of the National Bison Range said things like this:

MALE VOICE: It only makes sense that the CSKT be in full control of the heart of their reservation.

FEMALE VOICE: I am in full support of CSKT management of the bison range, in light of the tribes’ time-honored care and respect for bison.

MALE VOICE: Giving the bison range to the CSKT is not only a good idea, it is justice long delayed. They will do a terrific job managing it, and incorporating it into their cultural heritage. And I’m an old white guy!

AMY: The National Bison Range is kind of a microcosm of our whole country. These rolling hills hold all kinds of beauty, wildness, and stories of people with vision and courage. But they also hold our legacy of arrogance, violence, and racism. It’s all mixed together, and looking at the ugliness is painful. But so is denying it.

SOUND: Bugs chirping

AMY: I’m back at the bison range overlook with Rob McDonald and Rich Janssen. And Rob says for him, reckoning with the whole story here is as much about the future as it is about the past.

ROB: I think you’re looking at two of many survivors from that long history.

SOUND: Car driving by

ROB: There was an effort to destroy the native. It became an effort to destroy the culture. It became an effort to destroy their lands. It became an effort to destroy any vestige of the language and culture. And yet we're still here. It's pretty incredible, the survival story you're looking at that somehow through all of this – and we hear the stories of our parents or grandparents or great grandparents of....frankly being right at the brink of not making it – but yet somehow we're here and we're growing, and we're getting stronger. We're getting smarter. Well, I don't if we’re getting smarter but we're learning new tools.

AMY: And do you see that the bison that are wandering around are behind me, I mean, is that part of that survival story?

RICH: I'd most definitely say that that is the case.

AMY: This is Rich again.

RICH: I mean the bison survived almost being decimated. And you look at them now they're thriving. They’re still thriving.

MUSIC

RICH: You know the time is now. It’s a long time coming, for this to happen. And I’m pretty proud to say that I’m going to be a part of history. It's going to be a historic day indeed.

MUSIC

ROB: It’s just what we do. It’s what we've always done. And what we're going to continue to do. Protect the land, protect the bison, continue to grow into our original selves. Recapturing the culture, the language. And...it sounds like there’s a lot of naysayers out there, but we don’t listen to them.

MUSIC

AMY: We have links to the draft legislation and whole lot more at our website, thresholdpodcast.org. And we’re going to be tracking all of the unfolding stories here – the lawsuit, the environmental impact statement, and any legislative action. If you’re subscribed to Threshold you will get updates from us on all of these things. And make sure to tune in next time because I’m pretty sure we’re the only podcast giving you hot tips on how to get bison to move off your lawn.

DANI: We were playing rock-and-roll music really loud and bagpipe music

AMY: Were they more likely to move when they heard rock or when they heard bagpipes?

DANI: Bagpipes worked better (laughs)

AMY: That’s Dani Hatfield, she’s 17. You'll meet her and other kids who are growing up with wild bison, next time, on Threshold.

MUSIC

Credits

AMY: Threshold is produced by me, Amy Martin, with help from Nora Saks, Jackson Barnett, Zoe Rom, Nick Mott, and Josh Burnham. Special thanks to Michael Wright, Jessica Fjeld, Daniel Etcovitch, Christopher Bavitz, Audrey Adu-Appiah, and Mike Meloy for their help on this episode. Music by Travis Yost.

Threshold Newsletter

Sign up to learn about what we're working on and stay connected to us between seasons.